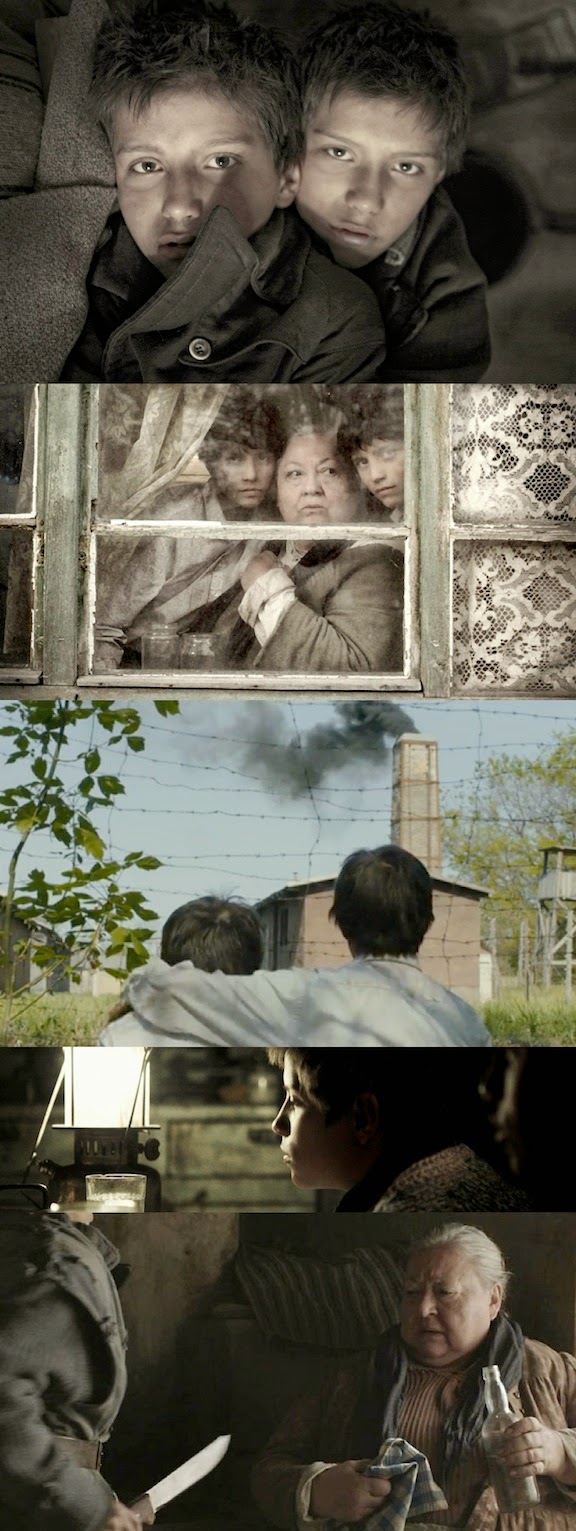

The Notebook (AKA "A nagy füzet")

Dir. János Szász (2013)

Starring: László Gyémánt, András Gyémánt, Piroska Molnár, Ulrich Thomsen, Ulrich Matthes, Gyöngyvér Bognár, Orsolya Tóth, János Derzsi, Diána Kiss

Review By Greg Klymkiw

Films depicting the horrors of war take on added resonance when they focus upon the innocence of childhood and, like Rene Clement's Forbidden Games or Steven Spielberg's Empire of the Sun, they're especially horrific when they focus upon the sort of insanity which grips children within the fevered backdrop of combat.

János Szász's The Notebook (AKA "A nagy füzet"), based upon the late Agota Kristof's award-winning 1986 novel, is replete with Eastern European rural repression as well as the inevitability that "freedom" from Nazism will lead to yet another form of Totalitarian rule. As such, it's a film that delivers several added layers of pain which represents a reality that all children have and will continue to experience so long as war is as much a part of human existence as breathing is.

The Notebook takes place during the final years of WWII in Hungary and focuses upon a seemingly inevitable decision a family must make that affects their children forever. With war still raging, a mother (Gyöngyvér Bognár) and father (Ulrich Matthes) decide it might be best to remove their sons (László Gyémánt, András Gyémánt) from the city.

Dad is a soldier and is especially adamant the boys be separated as they're twins and stick out more than most siblings. The mother will hear none of that since the boys are inseparable and instead transports them deep into the countryside to stay with her long-estranged and widowed mother (Piroska Molnár) who is placed in the position of being their reluctant Grandmother.

The boys are devastated to be left behind with this abusive, nasty-spirited old woman (referred by the those living in the nearby village as "The Witch"). She makes it clear to the lads that they will be forced to work her farm and earn their food and lodgings. In addition to beating them on a regular basis, referring to them only as "bastards", she tops off her cruelty towards the boys by leaving them locked outside in the cold.

Soon, the twins realize they will have to learn to survive at all costs.

They perform their chores with the same rapt attention they pay to their studies (from an encyclopaedia and Holy Bible) as well as the detailed writings of their experiences in a notebook supplied by their father who previously asked them to recount their lives in his absence. Survival, though, means learning to steal, withstand physical pain and eventually, to kill.

Especially moving, though in a odd and unexpected way, is the mutual love and respect that develops between the twins and their grandmother. They admire her tenacious survival mode and she, in turn, their steely resolve (and inherent nastiness), which she comes to grudgingly recognize in terms of their blood ties (and in spite of hating her daughter for abandoning the village so long ago).

The boys befriend a variety of locals, all of whom contribute in some way to their knowledge, survival and/or experience. An S.S. commandant (Ulrich Thomsen) from a nearby concentration camp takes a liking to them and becomes their unlikeliest protector, a facially disfigured teenage girl the boys cruelly call Hairlip (Orsolya Tóth) teaches them how to steal, a Jewish shoemaker (János Derzsi) who takes pity on them outfits the boys with winter boots and finally a maid (Diána Kiss) bathes the filthy, lice-ridden lads and even considers the possibly of introducing them to the pleasures of the flesh - these are but a few of the primary individuals whose paths the boys cross.

Amidst this strange world, the twins face adulthood through the skewed perspective of war and gain maturity long before they should. Sadly, it's a demented maturity, influenced by the horrors around them. They discover love of family where they least expect it, they reject another aspect of family love they'd never have imagined doing before the war and indeed, they kill and kill willingly - not because they especially want to, but because the circumstances demand it. (They do, however, want to kill one person and succeed in facially disfiguring this person in retaliation for giving up the Jewish shoemaker to the Nazis.)

The Notebook is an extraordinary experience. Screenwriter-Director János Szász elicits a series of performances that sear themselves into one's memory and he delivers a stark, haunting and devastating film by presenting some of the most horrendous acts of inhumanity in an oddly straightforward way, adorned only by the straight, unemotional narration through the boys' voiceover as written in their notebook.

Horror in this world, seen through the eyes of children, is presented as a simple matter of fact and this might be the most moving and disturbing thing of all. It's about children forcing themselves to not feel pain, to suppress all emotion and to never, ever cry. It's a film that might well be set in World War II, but it's as vital to the horrific world we now live in as if the events recounted were happening now. Most shocking and telling is the portrayal of Russian soldiers as the "liberators" of Hungary - marching in after the Nazis flee, but then, as Russians are won't to do, achieving little but stealing from the Hungarian farmers, hunting down anti-communist Hungarians as if they were war criminals and at one point, gang raping a young woman and murdering her for pleasure.

Not only do the boys learn there's no room for tears, but "liberator" is just another word for "oppressor".

The Notebook is a Mongrel Media release currently unspooling at the TIFF Bell Lightbox.

Dir. János Szász (2013)

Starring: László Gyémánt, András Gyémánt, Piroska Molnár, Ulrich Thomsen, Ulrich Matthes, Gyöngyvér Bognár, Orsolya Tóth, János Derzsi, Diána Kiss

Review By Greg Klymkiw

Films depicting the horrors of war take on added resonance when they focus upon the innocence of childhood and, like Rene Clement's Forbidden Games or Steven Spielberg's Empire of the Sun, they're especially horrific when they focus upon the sort of insanity which grips children within the fevered backdrop of combat.

János Szász's The Notebook (AKA "A nagy füzet"), based upon the late Agota Kristof's award-winning 1986 novel, is replete with Eastern European rural repression as well as the inevitability that "freedom" from Nazism will lead to yet another form of Totalitarian rule. As such, it's a film that delivers several added layers of pain which represents a reality that all children have and will continue to experience so long as war is as much a part of human existence as breathing is.

The Notebook takes place during the final years of WWII in Hungary and focuses upon a seemingly inevitable decision a family must make that affects their children forever. With war still raging, a mother (Gyöngyvér Bognár) and father (Ulrich Matthes) decide it might be best to remove their sons (László Gyémánt, András Gyémánt) from the city.

Dad is a soldier and is especially adamant the boys be separated as they're twins and stick out more than most siblings. The mother will hear none of that since the boys are inseparable and instead transports them deep into the countryside to stay with her long-estranged and widowed mother (Piroska Molnár) who is placed in the position of being their reluctant Grandmother.

The boys are devastated to be left behind with this abusive, nasty-spirited old woman (referred by the those living in the nearby village as "The Witch"). She makes it clear to the lads that they will be forced to work her farm and earn their food and lodgings. In addition to beating them on a regular basis, referring to them only as "bastards", she tops off her cruelty towards the boys by leaving them locked outside in the cold.

Soon, the twins realize they will have to learn to survive at all costs.

They perform their chores with the same rapt attention they pay to their studies (from an encyclopaedia and Holy Bible) as well as the detailed writings of their experiences in a notebook supplied by their father who previously asked them to recount their lives in his absence. Survival, though, means learning to steal, withstand physical pain and eventually, to kill.

Especially moving, though in a odd and unexpected way, is the mutual love and respect that develops between the twins and their grandmother. They admire her tenacious survival mode and she, in turn, their steely resolve (and inherent nastiness), which she comes to grudgingly recognize in terms of their blood ties (and in spite of hating her daughter for abandoning the village so long ago).

The boys befriend a variety of locals, all of whom contribute in some way to their knowledge, survival and/or experience. An S.S. commandant (Ulrich Thomsen) from a nearby concentration camp takes a liking to them and becomes their unlikeliest protector, a facially disfigured teenage girl the boys cruelly call Hairlip (Orsolya Tóth) teaches them how to steal, a Jewish shoemaker (János Derzsi) who takes pity on them outfits the boys with winter boots and finally a maid (Diána Kiss) bathes the filthy, lice-ridden lads and even considers the possibly of introducing them to the pleasures of the flesh - these are but a few of the primary individuals whose paths the boys cross.

Amidst this strange world, the twins face adulthood through the skewed perspective of war and gain maturity long before they should. Sadly, it's a demented maturity, influenced by the horrors around them. They discover love of family where they least expect it, they reject another aspect of family love they'd never have imagined doing before the war and indeed, they kill and kill willingly - not because they especially want to, but because the circumstances demand it. (They do, however, want to kill one person and succeed in facially disfiguring this person in retaliation for giving up the Jewish shoemaker to the Nazis.)

The Notebook is an extraordinary experience. Screenwriter-Director János Szász elicits a series of performances that sear themselves into one's memory and he delivers a stark, haunting and devastating film by presenting some of the most horrendous acts of inhumanity in an oddly straightforward way, adorned only by the straight, unemotional narration through the boys' voiceover as written in their notebook.

Horror in this world, seen through the eyes of children, is presented as a simple matter of fact and this might be the most moving and disturbing thing of all. It's about children forcing themselves to not feel pain, to suppress all emotion and to never, ever cry. It's a film that might well be set in World War II, but it's as vital to the horrific world we now live in as if the events recounted were happening now. Most shocking and telling is the portrayal of Russian soldiers as the "liberators" of Hungary - marching in after the Nazis flee, but then, as Russians are won't to do, achieving little but stealing from the Hungarian farmers, hunting down anti-communist Hungarians as if they were war criminals and at one point, gang raping a young woman and murdering her for pleasure.

Not only do the boys learn there's no room for tears, but "liberator" is just another word for "oppressor".

The Notebook is a Mongrel Media release currently unspooling at the TIFF Bell Lightbox.